History and profile of the manuscripts

Mmmonk reunites the ca. 820 surviving books of the former abbeys of Ten Duinen, Ter Doest, Saint Bavo and Saint Peter. Read here in a nutshell how the libraries came to be and what happened to the books over the past 1,400 years.

The first centuries of St Peter’s and St Bavo’s (ca. 630–ca. 1100)

The abbeys of St Bavo and St Peter were founded in the 7th century. A library was probably built up from the very beginnings of these abbeys, since the daily lectio divina and choral prayer were an integral part of Benedictine culture. Hardly any books have survived from those first centuries, but it may be assumed that the abbeys possessed at the very least biblical and liturgical texts, works by the Church Fathers, and the lives of the saints. Some examples from the earliest centuries of St Peter’s and St Bavo’s include:

- Hieronymus, Epistola 147; 6th or 7th century, St Peter’s Abbey (Ghent, UB, HS.0246)

- Antiphonarium Blandiniensis; 8th century, St Bavo’s Abbey (Brussels, KBR, ms. 10127-44)

- Evangeliary of St Livinus; 9th century, St Bavo’s Abbey (Ghent, BA, ms. 13)

- St Augustine, Confessiones; 10th century, St Peter’s Abbey (Paris, BnF, ms. lat. 1913A)

Two back bound endpapers of manuscript 246 of the Ghent University Library contain the oldest known fragments of a letter of Hieronymus, in beautiful semi-uncial script of the 6th-7th century.

(Ghent, University Library, Hs. 246, ff. 96v-97r)

Abbeys are centres not only of spirituality, but also of intellectual study. Thanks to the influence of Cassiodorus (ca. 485–ca. 585), monks and nuns were expected to study both ecclesiastical and secular science. At St Peter’s Abbey, this precept led to a highly developed and renowned abbey school. From the 10th century onwards, a library with a rich collection of classical authors was built to support this school. Abbot Wichard (r. 1034/35–1058) further expanded the library’s collection and scriptorium.

- Terence, Comoediae VI; 11th century, St Peter’s Abbey; copied by Wichard or members of his scriptorium (Leiden, UB, Lip 26)

The beginnings of the libraries of Ten Duinen and Ter Doest (ca. 1138–ca. 1225)

The Benedictine abbeys in Ghent, St Bavo’s and St Peter’s, were already about half a millennium old when the Cistercian abbeys of Ten Duinen (1138) and Ter Doest (ca. 1175) came into being. These new abbeys also began building up a collection of books from their earliest days. The 12th century was the heyday of scriptoria in the Low Countries. In Ten Duinen and Ter Doest, monks likewise set to work copying texts. In addition, they acquired books through donations, e.g., from the Chapter of St Donatian in Bruges, and by appealing to their Cistercian network, e.g., the mother institution in Clairvaux.

- De musica with glosses; Enchirias; De organo, Boethius; 10th-11th century, Ten Duinen; probably the oldest preserved manuscript from Ten Duinen (Brugge, OB, Ms. 531)

- Bible of Ter Doest; 13th century, Ter Doest; copied in Ter Doest by the lay brother Henricus and probably illuminated around 1265–1270 by a layman known as the Dampierre Master (Bruges, GS, Ms. 4/1)

In the abbeys of St Peter and St Bavo, monks also continued to copy and illuminate books, and books were acquired from outside.

- Ordinary of St Peter’s Abbey; 12th century, St Peter’s Abbey (Brussels, KBR, ms. 1505-06)

- Liber floridus, Lambert of St Omer; 12th century, St Peter’s Abbey (Ghent, UB, hs. 92)

The Liber floridus is an encyclopedia written by Lambertus, a cannon of the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk of Sint-Omaars in the beginning of the twelfth century. The Ghent University Library owns the autograph of this work.

(Ghent, University Library, Hs. 92, f. 13r)

13th and 14th centuries

With the rise of universities, scholasticism, mendicant orders, and the increase in private book ownership, abbeys lost their status as the main producers, distributors and keepers of books from the 13th century onward. Nevertheless, they continued to expand their libraries into the late Middle Ages. Ten Duinen and Ter Doest, for example, kept their finger on the pulse of current debates and insights thanks to contemporary copies of 13th-century scholastics such as Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas and Henricus of Ghent. Earlier experimental scholarly tracts such as those of the 14th-century Oxford Calculators are also present in very early copies at Ten Duinen and Ter Doest, indicating a certain intellectual openness.

Bibliophilic abbots in the 15th century

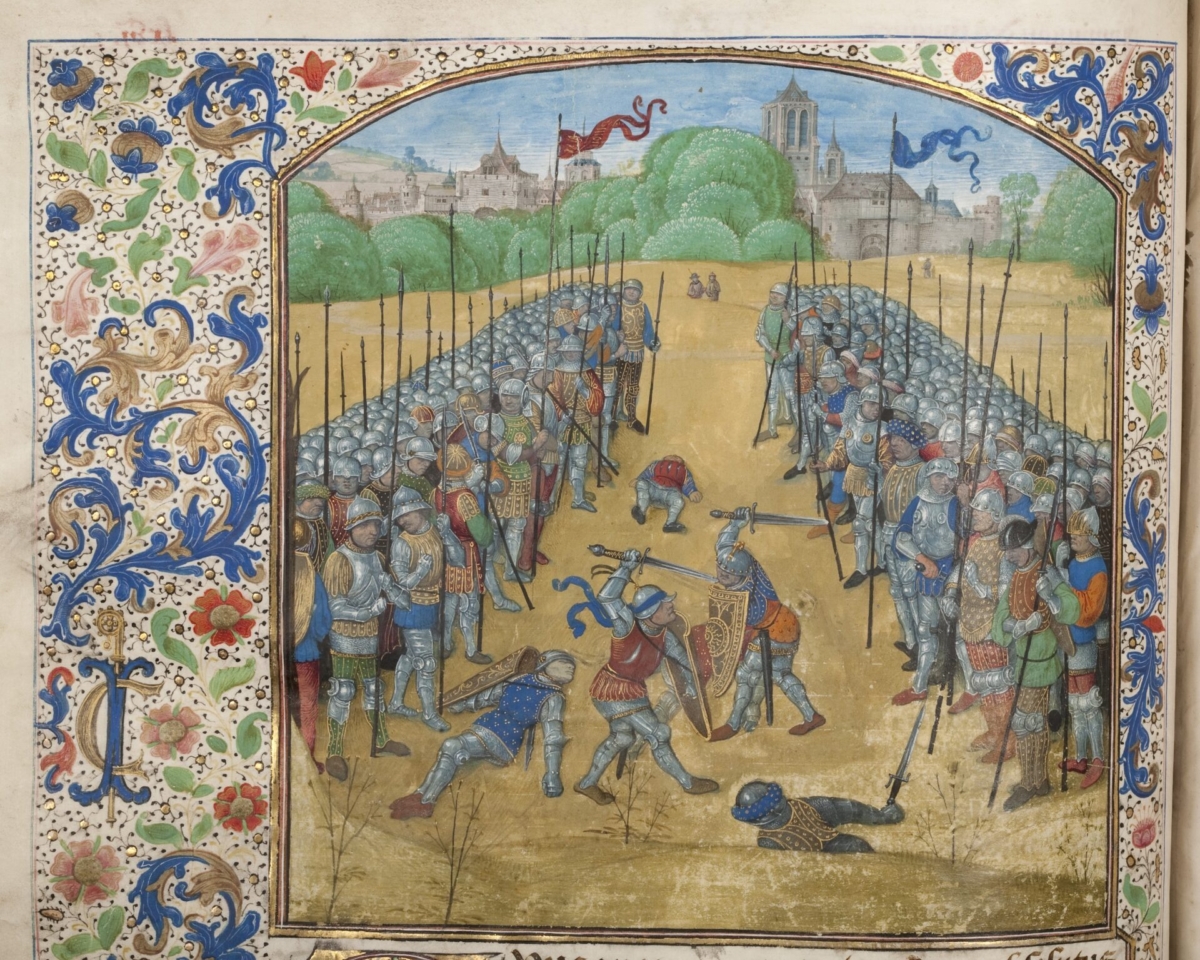

In the 15th century, several abbots played a role in the expansion of the abbeys’ book holdings. Abbot Philip I Conrault of St Peter’s Abbey (1444–1471), Abbot Jan Crabbe of Ten Duinen (1457–1488), Abbot Hendrik Keddekin of Ter Doest (1478–1491), and Abbot Raphael de Mercatel of St Bavo’s Abbey (1478–1508) are known bibliophiles and patrons. Like other bibliophiles of the Burgundian period, they favoured large, illuminated manuscripts that eventually found their way into the abbey library. Abbot Crabbe, for example, commissioned a three-volume copy of the Faits et dits mémorables of Valerius Maximus from the Bruges scribe and bookseller Colard Mansion, with miniatures by the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book.

They were also interested in the new intellectual movement of Italian humanism. They ordered books copied in a humanist or gothic-humanist script and had a preference for humanist texts. Abbot Raphael de Mercatel, for example, owned rare texts by Latin and Greek authors such as Plutarch, Aesop, Herodotus and Philostratus.

- Plutarch, De viris clarissimis; ca. 1478–1487, St Bavo’s Abbey (Ghent, UB, HS109); beginning of the chapter on Romulus (f. 11v)

This richly eluminated copy of Plutarch’s De viris clarissimis was made by abbot Raphael de Mercatel. Folio 115v contains the start of the life of the Romain hero Camillus. The miniature shows how the Celtic leader Brennus and his army set fire to Rome (387BC)

(Ghent, University Library, Hs. 109, ff. 115v-116r)

The tumultuous fate of the books after the Middle Ages

The abbeys had a difficult time in the 16th century. St Bavo’s Abbey was abolished and reformed into a chapter that was assigned St John’s Church (now St Bavo’s Cathedral) as its college church. In the process, all possessions, including the books, were transferred to the chapter. The buildings were dismantled at the behest of Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, to make way for the construction of a citadel.

The libraries of Ten Duinen and St Peter’s were looted during the spates of iconoclasm of 1566 and 1578-1584. A 1567 report on the damage at Ten Duinen Abbey, for example, notes that the iconoclasts burnt or stole the liturgical books. The abbey community tried to save the books by housing them in shelters, among other places in Veurne. Some of these books were indeed recovered in the 17th century thanks to the efforts of monk/detective Johannes Troch (1551–1612), but for some books this meant permanent separation from the abbey library. Because the coming of the first iconoclasm was foreseen at St Peter’s Abbey, many works of art could—fortunately—be brought to safety beforehand.

The library of Ter Doest was the only one to make it through the 16th century relatively unscathed. In 1624, however, the abbey of Ter Doest was dissolved and incorporated into Ten Duinen. Ter Doest’s extensive book collection was added to that of Ten Duinen.

Eventually, the two remaining abbeys, St Peter’s and Ten Duinen, suffered a fate that is characteristic of the history of Flanders. They were disbanded in the French Revolution and the manuscripts in their libraries were scattered. A large number were nationalized to supply the libraries of the Écoles Centrales. After 1804, the manuscripts were transferred to the local administrations of Bruges and Ghent.

In Bruges, this constitutes the historical origin of the public library’s heritage collection. The books were housed in the Gothic Hall of city hall. In 1884 they moved to the Tolhuis on Jan Van Eyckplein, and in 1896 they finally ended up in the Biekorf on Kuipersstraat.

In Ghent, the books also ended up in the municipal library, housed in the former Baudeloo Abbey. After the founding of Ghent University (1817), management of the library was transferred to the university. At the end of the 1930s, the municipal library and the university library were separated and in 1942, the manuscripts were moved to the new Book Tower designed by Henry van de Velde.

Some of the monastic books—not coincidentally, the most luxurious volumes—were hidden from the French occupiers. In Bruges, the hidden manuscripts of Ten Duinen ended up in the hands of the diocese and were eventually housed in Major Seminary Ten Duinen. In Ghent, the books were hidden by the canons of the episcopal chapter of St Bavo’s and by the (temporarily dissolved) Diocese of Ghent.

(Evelien Hauwaerts, 2021, for Mmmonk.be)