Abbot Mercatellis

Abbot Raphael de Mercatellis

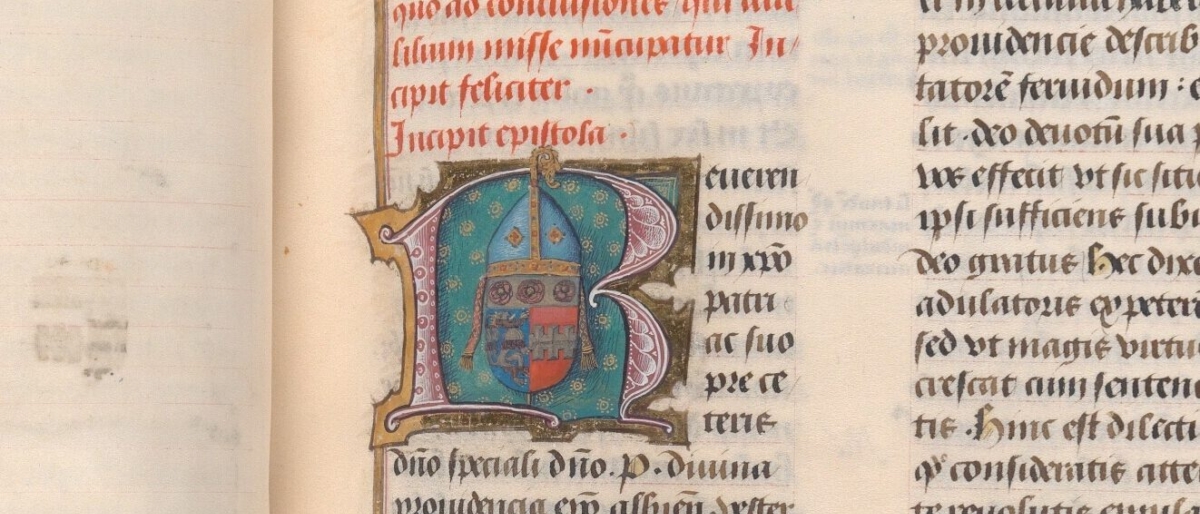

Raphael de Mercatellis. This particularly exotic name was borne by a bibliophilic Burgundian who, as abbot of St Bavo’s Abbey, assembled the most important humanist library in the Low Countries before the 16th century.

Illegitimate son of Philip the Good

He was born in Bruges in 1437. We know next to nothing about his mother except that she married Bernardus Mercadelli de Mercadello, a Bruges-based scion of a Venetian merchant family. Raphael de Mercatellis inherited his name. A bastard of Duke Philip the Good, he could count on a place in the Benedictine St Peter’s Abbey in Ghent, whence he could study theology in Paris. In 1462, he obtained the degree of magister in theology and a year later, in 1463, as a young man of 27, he was appointed abbot of St Peter’s Abbey in Oudenburg (between Bruges and Ostend).

Burgundian and Italian

In retrospect, it is very tempting to point out that Raphael spent his whole life passionately seeking to achieve osmosis between the backgrounds of his adoptive and biological fathers: Italian humanism on the one hand, and the Burgundian bibliophilia of which Philip the Good is the very embodiment.

Abbot at St Peter’s Abbey in Oudenburg

Even for those not so keen on reductionist psycho-biographies, the period in Oudenburg from 1463 to 1478 is crucial in the genesis of Raphael de Mercatellis’s personality. There, he crossed the path of Jan van der Veren, or Johannes de Veris, who was not insignificant in the development of humanism in Flanders.

Abbot Mercatellis and De Veris developed an Oudenburg school. Their collaboration did not last long, because Jan van der Veren disappears from the historical scene as early as 1469, but the impression he made was a lasting one. Texts by De Veris turn up decades later in manuscripts produced for De Mercatellis. Our abbot scarcely cared for his monastic community; instead, he was seized by a bibliophilic collecting frenzy that, according to some, verged on megalomania.

Abbey income spent on a lavish lifestyle

Detailed archival research shows that De Mercatellis tried in every possible way to boost the abbey’s income. However, he did not do this to look after his community as a responsible abbot. For example, it took ages before the necessary works were carried out on the roof of the abbey refectory to stop the rain coming in. Rather, the abbot was known for his lavish lifestyle—to the extent that he turns up in archival documents because of his presence at many feasts and his particular purchasing prowess … which of course included buying very large, expensive, luxurious illuminated manuscripts.

Abbot of St Bavo’s Abbey in Ghent and auxiliary bishop of Tournai

This policy was onerously balanced for Oudenburg Abbey, yet in 1478, thanks to his connections at the Burgundian court, Raphael de Mercatellis was able to secure an appointment as abbot of St Bavo’s Abbey in Ghent and, later, a lucrative appointment as auxiliary bishop of Tournai. All of which indicates his nose for political influence and connections. He was particularly active on that front throughout his life.

A nose for luxury

His bibliophilic collecting frenzy reached a crescendo during his three decades as abbot of St Bavo’s Abbey from 1478 to 1507. He spent years building what would become the most important humanist library in the Low Countries before the 16th century. That the abbey and its monks suffered as a result is beyond doubt. The cost of commissioning manuscripts was extremely high and, moreover, Mercatellis’s spending habits remained excessive. So he built a house of refuge for St Bavo’s Abbey in Bruges on the Garenmarkt. It became his main residence until he died there in 1508. As befits a veritable state funeral avant la lettre, his body was transported from Bruges to Ghent by 100 horses. Years earlier, he had ordered a breathtakingly expensive funerary monument from a Bruges stonemason.

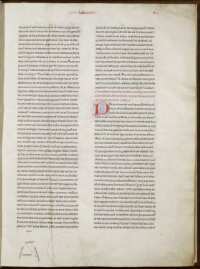

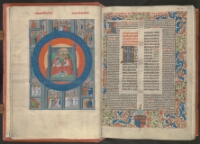

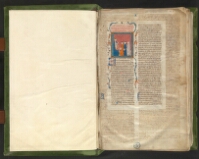

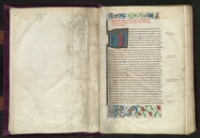

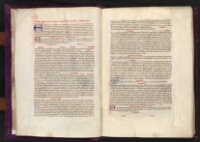

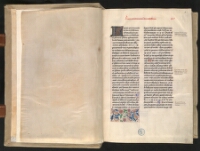

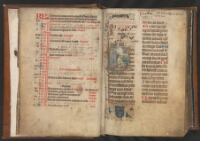

100% written and illuminated to order

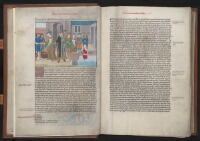

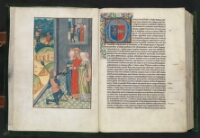

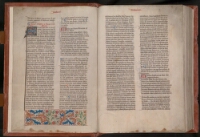

For anyone concerned with how history will deal with his or her legacy, it is particularly revelatory that virtually nothing has survived of De Mercatellis’s worldly extravagance and political missions for the Burgundian court. What has survived and is cherished throughout the world to this day are the results of his investments in illuminated manuscripts, or investments in heritage. Indeed, Raphael de Mercatellis’s library was and is unique. It is the only medieval collection—north of the Alps, of course (!)—consisting exclusively of manuscripts written and illuminated to order. They were all produced to the same standards in large format on luxurious parchment in specialized workshops in Bruges and Ghent. At that time, those cities were absolutely world class in this respect.

Humanistic, classical, and scientific texts

Only in De Mercatellis’s collection could one find so many manuscript texts from Antiquity and the Italian Renaissance together in one library. Also noteworthy is his exceptional interest in science and occult science (the distinction between the two was not so clear at the time). While religious manuscripts were dominant everywhere, in the library of Abbot Raphael de Mercatellis they constituted an insignificant minority. With our bibliophilic Burgundian bastard, we find texts by or about Cicero, Seneca, Homer, Pythagoras, Boethius, Plutarch, Herodotus, Thucydides, Aristotle, Virgil, Boccaccio, Petrarch … There are, of course, a few biblical commentaries, but the abbot did not possess a Bible or book of hours in manuscript form.

The manuscripts after De Mercatellis’s death

The collection is extremely rich and offers numerous opportunities for research into writing styles and codicological details, but much more interesting is the fate of the collection after the abbot’s death. After the destruction of St Bavo’s Abbey in 1540, the library collection moved with its monastic community, but while it was protected from the violence of iconoclasts in 1566, this was not the case in 1578. Some of the works held in Haarlem today were probably acquired during their raids.

However, the canons of the Chapter of St Bavo themselves were the greatest engine of the collection’s dispersal. Not only did they sell to private collectors and bibliophiles, but in May 1680 they decided to furnish the library as a waiting room, the cost being covered by the sale of a large number of works from the collection. The Earl of Leicester was willing to pay a considerable sum for what the chapter described as “obsolete works that are not used anyway.” The fifteen manuscripts in question remain showpieces in Holkham Hall’s collection to this day.

And the confiscation of church property by the French Revolution was yet to come. Thanks to Karel van Hulthem, a treasure trove of Ghent’s library heritage escaped being carted off to Paris. Instead, twenty years later, in 1817, it ended up in the Library of Ghent University via the city’s donation to the university.

Now preserved in Ghent …

In the Boekentoren (“Book Tower”, Ghent University’s main library building), we manage 21 De Mercatellis manuscripts to date. On the occasion of the retirement of my predecessor and specialist on the subject, Albert Derolez, a fragment of a 22nd codex was also donated to the University Library by one of his colleagues. After winds of Revolution had died down, the Chapter of St Bavo also looked after seven manuscripts from the collection that had been successfully hidden or placed in the custody of confidants.

… and much further afield

Like so many collections in the wake of the French Revolution, the rest were scattered all over the world: from the art library in Berlin to the Bibliotheca Durazzo Giustiniani in Genoa, from Peter House in Cambridge to the British Library in London, from our own Royal Library in Brussels to the University Library in Chicago, from the Bibliotheca Colombina in Seville to the Bodleian in Oxford … and the list goes on. All of them are collecting institutions that treasure this Flemish heritage. Today we know the location of some 65 of the 100 codices. In November 2013, all codices preserved in Flanders were recognized as masterpieces by the Flemish Community.

(Hendrik Defoort, 2022.)

Mercatellis' manuscripts

- Aylesbury, Waddesdon Manor, 15 (Coll. Rothschild)

- Berlijn Kunstbibliothek, 4005-03, 185

- Berlijn Staatsbibliothek, Lat. fol. 25

- Brugge, Bisdom, A128

- Brussel, KBR, 14887

- Cambridge (MA), Houghton Library Harvard University, Typ 95

- Cambridge, Peterhouse (University Library), 269

- Chicago, Art Institute (Ryerson & Burnham Libraries), 15334

- Chicago, University Library, 707

- Genova, B. Durazzo Giustiniani, A VII 12

- Genova, B. Durazzo Giustiniani, A VII 13

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 9

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 10

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 11

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 12

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 14

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 15

- Gent, Kathedraal, Ms. 16

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 1

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 2

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 3 vol. I

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 3 vol. II

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 3 vol. III

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 5

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 7

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 10

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 11 vol. I

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 11 vol. II

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 13

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 17

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 21

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 62

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 67

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 68

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 69

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 70

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 71

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 72

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 77

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 109

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 112

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 134

- Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs. 4179

- Glasgow, University Library, GLASC MS Hunter 206

- Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek, 187 C 11

- Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek, 187 C 13

- Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek, 187 C 14

- Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek, 187 C 6

- Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek, 187 C 7

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 128

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 133

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 168

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 218

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 318

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 324

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 406

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 407

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 413

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 442

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 443

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 448

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 449

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 490

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 216 vol. I

- Holkham Hall (L. of the Earl of Leicester), Ms. 216 vol. II

- London, British Library, Add MS 17381

- London, British Library, Arundel MS 93

- London, British Library, Harley 2678

- New Haven (CT), Beinecke Library, Ms. Mellon 25

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, N. acq. lat. 2460

- Sevilla, B. Capitular y Colombina, 82.7.14

- Sevilla, University Library, 330/154

- Sevilla, University Library, 332/155

- Sevilla, University Library, 332/156

- Toledo (OH), Museum of Art, 15

(Evelien Hauwaerts, 2022.)

Manuscripts in this collection

View more manuscripts and collections

Abbot Crabbe